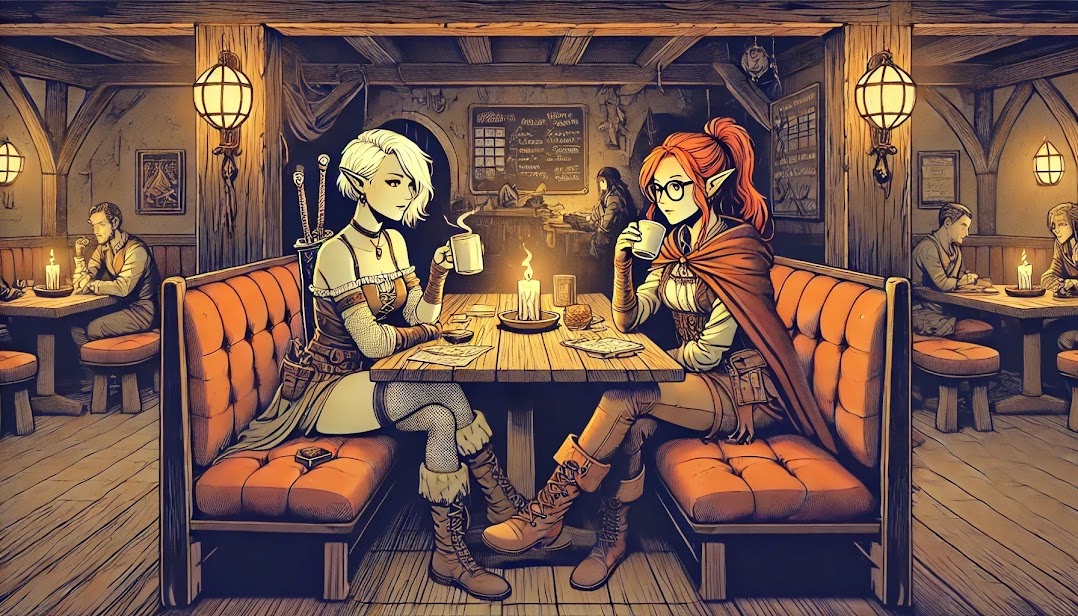

Pour House

Where Most Great Adventures Begin and End

"I once had stew, cake, spiced eggs, and sweet pickles in one sitting. The cook didn’t blink. Just asked if I wanted dessert."

In the long shadow of the Arin Civil War, when the fires had cooled and the final dead were buried, Areeott entered a period not of triumph, but of slow, determined healing. Fields were replanted, roads rebuilt. Families gathered what remained and chose to begin again. Amidst this quiet reconstruction, a new institution quietly rooted itself into the everyday rhythm of life: the Pour House. Neither tavern nor inn, and possessing none of the fine airs of a noble dining hall, Pour Houses were something else entirely—something humbler, softer, and infinitely more necessary. They are not called Pour Houses because of what is poured, but because of what is offered. Soup from the ladle, coffee from the pot, tea, syrup, broth, stew—hot, cold, spiced or plain, poured from whatever was on hand into whatever could hold it. The name became vernacular almost instantly. It said everything and explained nothing. Everyone in Areeott simply understood what it meant: if you were tired, hungry, cold, lost, alone, or just didn’t want to go home yet, the Pour House would have a seat, a plate, and no questions asked. These establishments cropped up in cities and towns first, then spread into the highlands and along mountain passes, until even the loneliest road seemed to have at least one place a traveler could duck into and emerge warm and fed. They were never designed as inns and would never be mistaken for one. There are no beds. There are no overnight stays. But a good Pour House can feel like the soft middle of the world—a place outside of time, smelling of coffee and grease and cinnamon, where an adventurer might plan a campaign or recover from one. Each Pour House is a reflection of its place and people. Some are narrow, tucked into stone alleys or the backs of buildings, open to the street and full of noise. Others sprawl across converted stables or old military mess halls, tables uneven, mismatched chairs gathered over decades. They are always open. Always. If a door is locked or a sign flipped to ‘closed,’ it means something terrible has happened and the neighborhood will already be talking. In most of Areeott, the day doesn't begin until the first pot is poured. There are no menus in the traditional sense. What’s available depends on the pantry, the cook’s mood, and what came off the delivery wagon that week. But there is always food. Something sweet, something savory, something starchy and filling, something light, something strong with spice. The Arin understand that what you eat for breakfast may be soup or steak or cake, and that is no one’s business but your own. Some places hand out battered slips of vellum with house favorites listed and half the items crossed out. Others use walls of chalkboards or simply shout across the room when you walk in. In all cases, the unspoken understanding is the same: sit down, we’ll feed you. Some Pour Houses are stricter about decorum. You eat what’s served, you pay, and you go. Others are much looser. You can bring in your own bottle, your own food, your own half-finished game of Dragonwatch and play until your dice wear down. So long as you keep ordering—another coffee, another plate of hearthcakes, another round of sweetroot sticks—no one will bother you. These places become second homes to the wandering and the weary. The booth in the corner might have hosted three generations of a mercenary band, who regrouped here after every campaign. That scratched tabletop? Dozens of lovers have carved initials into it, some paired, some crossed out, some trailing off into unintelligible lines. It’s not uncommon to see people sitting alone for hours. Reading, writing, mending gear, staring at the window without focus. Pour Houses make space for the in-between moments of life: after the bad news, before the apology, while you’re still deciding whether to leave town or stay another week. Some have bookshelves and old musical instruments. Others have memorabilia stuffed into nooks and nailed along rafters. A sword with a broken hilt. A signed portrait from some bard no one remembers. A green crystal egg that hums faintly and no one will touch. They are not temples, but they are sacred. They are not sanctuaries, but you are safe. Violence here is rare and dealt with swiftly, not by law or magic, but by the firm unspoken will of the people around you. Everyone knows the rule: you do not break the peace of a Pour House. Not in front of the coffee pot. And perhaps more than anything, they are Arin. Not in the nationalistic sense, but in the quiet, collective soul of a people who have suffered deeply and chosen, against all reason, to build something warm in the ashes. The Pour Houses of Areeott are not celebrated in song or preserved in history. But they endure. A place to sit, to eat, to be. Sometimes, that’s all you need.

Purpose / Function

"A Pour House is where you go when you don’t know where else to go. And sometimes, that’s the whole reason they exist."

The Pour House was never meant to be anything grand. Its purpose was simple from the beginning: to keep people warm and fed when no other door was open. It was born not from commerce, not from civic design, but from necessity in the quiet aftermath of war. During the Reconstruction Era that followed the Arin Civil War, communities needed a way to guarantee care without question or qualification. The noble houses offered protection, the temples offered prayer, but the people needed places that offered soup, a table, and a place to sit down, especially for those who had nothing else left. The earliest Pour Houses were nothing more than communal kitchens set up in abandoned taverns, carriage barns, or post stations. They were staffed by whoever had hands to cook and food to spare. There were no menus and no expectations. You showed up, you ate, you left something behind if you could—coin, labor, news, or silence. That was enough. Over time, the function of these spaces didn’t change, but their presence deepened. They became cultural anchors—not just shelters against the cold, but reliable gathering spots in every part of Areeott and into Kestenvale. Their role remains unchanged: to provide comfort, nourishment, and a moment of reprieve without ceremony or condition. A place for everyone and no one. A place that doesn’t ask what brought you in, only what you need before you leave.

Architecture

"That table sings at night. Just a little. If it hums under your elbows, don’t worry. Means you sat where someone loved someone else real hard."

Pour Houses are not bound to a single architectural style, but they are instantly recognizable by their function-first design and lived-in aesthetic. Their architecture varies widely by region, but all share a few common traits: accessibility, warmth, and informality. They are meant to be entered, not admired; used, not preserved. If a building looks too proud of itself, it’s probably not a real Pour House. In the mountain cantons of Areeott, most Pour Houses are built into existing stonework such as converted stables, defunct watch stations, low hall structures built from Agriss granite or riverstone. Walls tend to be thick, retaining heat in the long winters, with exposed beams of dark, weathered spruce or pine. Roofs are practical and steep for snow runoff, typically shingled in slate or hand-cut cedar. Doors are often oversized and framed with old horseshoes or iron stove parts nailed into the grain. There’s no uniformity, but there’s always a sense of wear—scrapes from boots, warping from heat, stains on the floors where something good boiled over a long time ago. In the valleys and southern reaches, especially as Pour Houses crept into Kestenvale, you start to see more wood construction such as poplar, oak, ash. Plank floors. Chimneys patched with river clay and sand. Siding is sometimes whitewashed or left to gray naturally, with paint in whatever color was available at the time it was built—there’s no standard, but door frames are often painted red, green, or ochre. These aren’t decorative choices so much as available leftovers, though a red door often means “always open, no questions.” People don’t decorate Pour Houses with an eye for beauty. They adorn them by leaving things behind. A spear that saved a man’s life. A carved piece of bone. An old traveler's hat mounted on a hook. Stained maps, etched knives, hand-painted signs in five languages saying "Yes, we’re open" or "Hot stew inside." The outside of a Pour House might have a battered sign, maybe a weather vane shaped like a frying pan, or a stone step worn smooth by a hundred thousand boots. There’s no ornament, only memory. Some of the oldest and most beloved ones have strange additions built onto them over the years; a second story that leans, a balcony that leads nowhere, a half-covered courtyard with benches salvaged from a retired tram line. In every case, the structure is shaped more by use than design. Form follows function, and the function is this: keep the kettle on, keep the door open, and always have a seat ready for whoever needs it.

History

"They say every Pour House has a booth that belongs to the dead. Not haunted. Just… reserved."

The first Pour Houses appeared in the early Reconstruction Era, in the quiet lull after the Arin Civil War when the land was scarred but finally still. In those years, Areeott was not yet stable, and many communities had been shattered: homes lost, families scattered, villages emptied. The roads were open again, but trust was not yet repaired. People needed warmth. They needed something familiar that didn’t ask for explanations.

In the beginning, these were improvised kitchens: hearths kept going by widows, retired soldiers, and old farmers who had just enough to share and no one left to share it with. They opened their doors, not as a business, but as an act of survival hospitality. A hot plate, a place to sit, something to drink, something to remind you the world wasn’t over. Travelers began calling them "Pour Houses" for the steady sound of soup or tea being ladled into whatever cup or bowl a person brought with them. As the years passed and the country slowly returned to prosperity, the Pour House model didn’t vanish. It matured. Municipalities began quietly supporting them with supplies. Trade guilds donated scrap, food, and tools. They were never codified in law, but local governments understood: a village without a Pour House wasn’t a village ready to live again. And so they spread. By the time the younger generation came of age, those who hadn’t fought in the war but had grown up hearing its stories, Pour Houses had become a natural fixture of daily life. Not a place to go in crisis anymore, but a place to stop in between the rest. They became the backdrop for mundane rituals: morning meals before a long hike, late-night coffee after bad news, birthday pie in a booth still scarred with sword marks from two generations ago. Some Pour Houses have been operating continuously since those early postwar years. Others have been rebuilt, expanded, even franchised in rare cases, but none have lost their grounding in that first instinct: the open door, the hot food, and the refusal to turn anyone away. They are not monuments to victory or symbols of power. They are the living proof that Areeott chose to rebuild itself with generosity and a stubborn kind of kindness.

Tourism

"One time I traded a state secret for a slice of strawberry tart and it was the best deal I ever made. Kingdom’s gone now.

Tart still haunts my dreams."

Pour Houses are not destinations in the traditional sense. They are not carved temples or grand keeps or famed battlefields. But for certain travelers, they are sacred all the same. Those who come seeking them are not tourists in the usual mold—they are wanderers, nostalgists, scholars, and veterans. People who travel not to see something new, but to touch something familiar. Some travelers make a point of visiting a Pour House in every canton they pass through, collecting meals instead of trinkets. Others seek out the oldest still-running establishments, looking for the legendary booths etched with names half-erased by time, or the stories left behind in mismatched cutlery and cracked mugs. A few make pilgrimages to specific Pour Houses tied to family memory or personal history: the place where a parent met a lover, where a company of adventurers swore an oath, where a wounded soldier waited out the end of the war. There’s no single Pour House aesthetic, but there is a shared experience people come to find: the warmth, the chatter, the soft scrape of plates and the smell of butter and starch and spice. The slow pace. The freedom to linger. Some travelers come to write, or read, or sit in silence. Others strike up conversations with strangers and add their names to the ever-growing mental ledgers kept by regulars and staff alike. Tourists who come to Areeott for the Pour Houses rarely plan their trips around accommodations. Most stay in nearby inns or boarding rooms—simple places, often within walking distance. The kind of quiet lodgings that pair well with a bottomless cup of coffee and an afternoon spent watching the weather change. No one stays in a Pour House, of course. That isn’t what they’re for. But those who know the culture understand: if you need a soft landing between travels, if you want to see Areeott as it truly is, you find the nearest Pour House, walk in, and take a seat like you’ve always belonged there.

"No one plans to stay long. And then it's dusk, and you're still at that same damn booth."

Comments